Seeing Them With Our Eyes

In photography, not all the rules are written. Yes, there are composition norms that inform sound artistic photography composition. However, those are not all the benchmarks that any serious photographer will require. Here is an example…

Within the Vatican Museum are thousands of works of various art forms. In a hall that connects the north and south wings of the museum’s upper floor, is a collection of busts sculpted throughout the chronology of the western Roman empire. While I appreciate fine sculptures, my ability to relate to the stone faces is limited. Further complicating this is that many of the Vatican’s busts are missing body parts or have substantial surface damage resulting from neglect.

A year ago, I undertook a photographic project to record the essence of the sculpted art form but do so in an innovative way. I sought to pose a question from a position of artistic humility: as a 21st century artist, how can I reflect the beauty of the sculpted art in a way that enhances its relatability?

The four image sets that follow are that photographic project. The first image set is of Commodus, son of famed emperor Marcus Aurelius. While numerous busts of Commodus survive, I found this bust the least over-the-top and most useful to anyone in this millennium who wanted to be able to pick Commodus out of a police lineup. The images that follow are taken with a Canon EOS-1DX Mark III DSLR paired with a 35mm portrait lens in aperture mode. The sepia tone is original to each bust.

Commodus Original

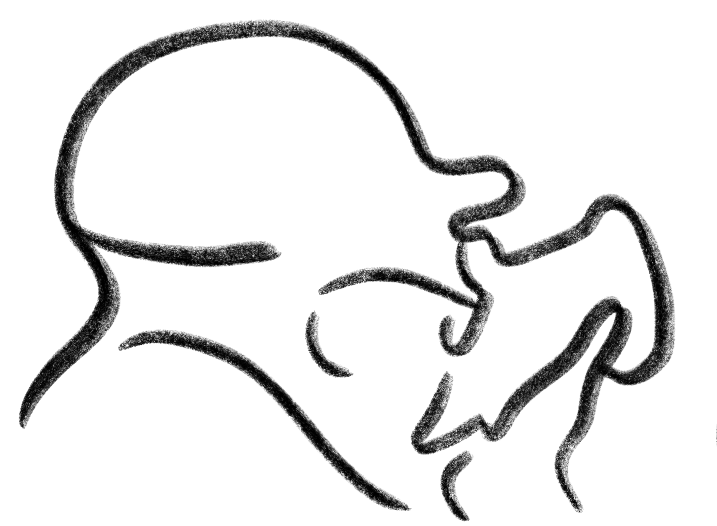

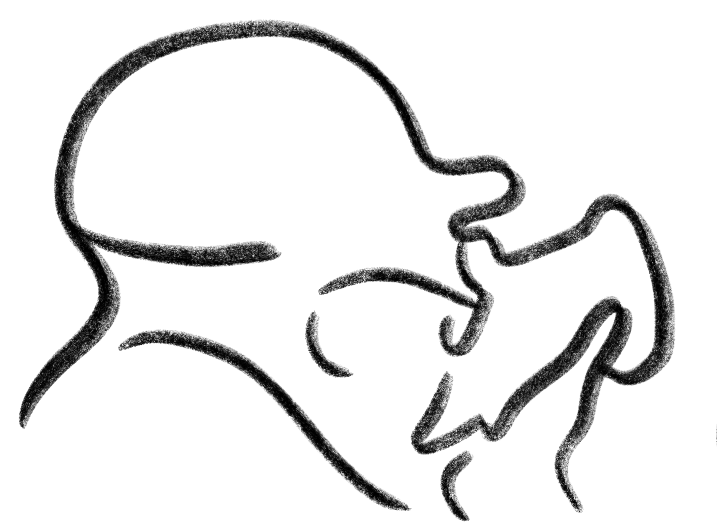

Commodus Interpreted

My interpretation of the original sculpture is the bust but with obvious enhancements. In my photographic experimentation associated with this project, I found that a pair of eyes—brown, took Commodus from a sculptural interpretation of a human to stone instantiated with a modest degree of humanity. The capability suite of my post-editing software softened the hewn stone on and around his face into marbleized renderings of hair then into hair recognizable to modern eyes. Interestingly, there is little in the bust that presaged Commodus’ descent into murderous insanity that in turn, culminated in his murder, in 192CE.

A Dacian

A Dacian Interpreted

The second picture set is based on a bust of A Dacian. The sculptor’s name is unknown as is the subject of the sculpture. In antiquity, Dacia was a sprawling land that began on the western shores of the Black Sea then stretched westward into lands which in this era correlate to Ukraine, Romania, eastern Hungary, northern Bulgaria, much of Moldova, and a majority of Serbia.

The original sculpture speaks to the features of an original subject with hard facial features. The image editing process softened that early harshness, added dark eyes, and relaxed the sculpture’s hair interpretation. What emerges, is an image which in my view enhances its relatability. It is a depiction of a man we might meet in the square or on the subway.

The third set depicts the emperor Hadrian. Commonly called the third of the “five good emperors,” he died in 138CE. Hadrian is renowned for his efforts for a first-ever functional unification of the Roman empire. The first image in this set of two is the bust found in the Vatican Museum, reproduced in numerous historical documents.

Hadrian Original

Hadrian Interpreted

Like the interpretive images in the previous sets, the addition of eyes makes a stone object—Hadrian’s face, more relatable to modern sensibility. While the imperfections in the stone are visible and the sculptor’s impressive rendering remains intact, the softening of the image’s face makes Hadrian come alive.

The fourth image set is Julia Domna. She and her husband, emperor Septimus Severus enjoyed a committed marriage that lasted for almost 25 years and produced two sons. While the first son of her marriage to Severus was named Augustus to better support Severus during his years of conquest absence from Rome, Julia had the power of empress dowager. She wielded consider political force in Rome and was a wise patron of Rome’s intelligentsia. This reinterpreted image of Julia takes the beauty depicted in the stone, adds eye color then slightly augments with a softened face accented by a decorative hair arrangement that conforms to the sculpture’s original hair.

Julia Original

Julia Interpreted

None of the interpretive photographic images should be construed as an attempt to perform unauthorized changes to the art’s original form or usurp sculptor intent. Instead, we have rendered images which aid relatability yet remain fully reflective of the original sculptural works of art. While not all sculptures lend themselves to a slight “modernization,” these four are ideal.